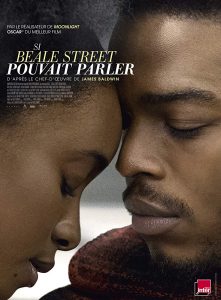

If Beale Street Could Talk ★★★½

If Beale Street Could Talk ★★★½

SOME directors never achieve a distinctive style and voice throughout their careers.

Barry Jenkins May have done it with just two films.

If Spike Lee continues to be the angry, didactic voice of black America, Jenkins provides the considered, lyrical one.

But he is also no less passionate in seeking to portray powerful and relevant stories of African-American lives on screen.

In his Academy Award winning 2017 film Moonlight, Jenkins explored with great sensitivity and substance three different aspects of masculinity.

in 2019’s If Beale Street Could Talk he turns his focus to the female perspective in adapting a celebrated novel by the late activist James Baldwyn.

While the film is set in 1970s’ Harlem, New York, Baldwyn’s original Memphis’ Beale Street represented every struggling neighbourhood of predominantly Afriacan-American residents seeking to create a sense of community, cohesion and voice in white-dominated society

While a male-female love affair is at the centre of the narrative, it is the female perspective that is most pronounced with the relationship seen through the eyes of the female central character, her mother and sister and their female in-laws.

Tish is 19 and Fonny 23. They have grown up as neighbourhood friends and now this has developed into a deeply loving relationship. When we meet them, they are lost in each others’ company, fully occupying each moment and place together.

But we learn quickly, through means of a flas-forward, that all is not well. Fonny is in prison awaiting trial for a crime that he could not have physically committed and Tish is pregnant.

The story is then told in three seemless timeframes – the present, with Tish dealing with the views of family members of the pregancy news and their capacity to raise a child; the immediate past, revealing the incident that leads to Fonny’s imprisonment; and the sections where time almost stands still when the couple first fell in love and become physically intimate.

The central relationship is beautifully presented and acted, the performances of KiKi Layne and Stephan James natural and passionate. If you told me they were partners in real life, I would not have been surprised.

Every performance in the film is nuanced and provides powerful moments, particularly Regina King as Tish’s mother Sharon, Colman Domingo as her father Joseph and Teyonah Parris as sister Ernestine. Two of the stand-out scenes involve the main cast discovering and dealingwith the news of Tish’s pregnancy.

There is also poignancy in the story of Fonny’s jailing, with the script treating the threat of imprisonment almost as an inevitable right of passage that a black man in America is forced to contend with at some stage of his life.

My only concern with the film is a by-product of its quiet strength.

The first half is visually arresting and engrossing in establishing its characters, but the examination of its themes occurs in sometimes too languid a pace during the second half. Jenkins tendds to focus on creating wonderfu;l individual scenes, rather than moving his narratives and themes forward as a whole.

Minor quibbles aside, this is a film that does indeed give a powerful voice to the people of Beale Streets all over America and perhaps other countries and cultures as well.